1.

There was a surprising moment in last year’s Into the Dalek when the new Doctor indulged in a bit of nostalgia. “See, all those years ago, when I began,” he ruminated, “I was just running. I called myself the Doctor, but it was just a name. And then I went to Skaro. And then I met you lot and I understood who I was. The Doctor was not the Daleks.”

50 years after it was broadcast, Doctor Who is still referencing The Daleks (if that’s what we’re calling it this week). And still expecting its audience to know about it. Which isn’t as naively optimistic as it sounds; after all this story’s also been a film, one of the most reprinted novelisations and completely remade as Genesis of the Daleks. This is Doctor Who‘s equivalent of a folk tale, being told again and again, changing as it goes.

But for Into the Dalek to claim that this is the adventure which defined the Doctor is a bit rich. Nothing of the sort happens in The Daleks. The Doctor (curmudgeonly William Hartnell) finishes this exciting adventure with the Daleks more or less as he starts it. He’s the same slightly shady, temperamental old git; there’s no transformative effect on his character. There’s no profound realisation about who he is. To claim there is is a nice thought and fits what we know now about his character. But it’s a revisionist view. Look to the next story, Inside the Spaceship, if that’s what we’re calling it this week, for the real change in who the Doctor is.

That snippet of dialogue from Into the Dalek does however accurately reference a transformative effect this story had its production team. As is well documented, the show’s creator, Sydney Newman, disliked this story and didn’t want it made. He thought its ‘bug eyed monsters’ too low rent. But when the story’s ratings skyrocketed, Newman, producer Verity Lambert and story editor David Whitaker suddenly knew what their audience wanted. Action, adventure and, yes it had to be admitted, bug eyed monsters. It was they who suddenly understood who the Doctor was.

2.

It’s funny watching this story with 50 years of hindsight, knowing the impact it will have on the series. Of course, it was never meant to be so influential. It was the only story the production team had ready to go. It was not planned as any more important a story than those surrounding it. The Daleks were meant to be one offs. In 1963, this was not the first Dalek story, but the only Dalek story.

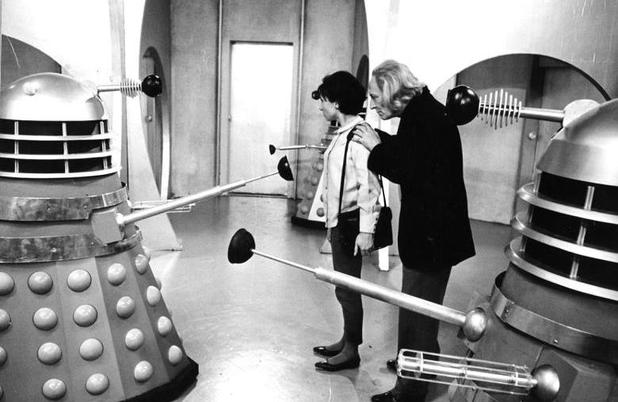

We can only imagine what it would have been like watching this for the first time. It must have been an extraordinary experience. Surely there was nothing on television like the Daleks. Even in these early days, when effects are still very ropey, they must have been eerily fascinating.

There’s a moment in An Adventure in Space and Time where we see the filming of this story, and the Daleks fill up the playback screens as unsettled crew members watch on. A Dalek’s camera lens eye stares unflinchingly out of the monitor. ‘They’re creepy‘, someone says and I imagine that’s the reaction felt by the viewing public at large. In 1963, these things were weird, nightmarish creatures but we’ve lost that sensation. These days, they’re familiar as family pets.

Back then, they made for must-see TV. 6.4m people watched The Daleks‘ second episode, where the monsters first appear. The following week that figure was 8.9m, up 40%. By the end of the serial, it was 10.4m. Numbers which ensured the show’s longevity. Like Newman’s dislike of BEMs, that ratings boost went down in Whostory. Fans tell each other these anecdotes over and over. Again, this story’s like a folk tale, within and outside its fictional world.

3.

Its political allusions are a little confusing. The Daleks have long been labelled Nazis, lurking in an underground bunker, talking of extermination. But it’s there that the similarities end, at least in this, their introductory story. The more interesting aspect of them is that they are the mutated remnants of a race ravaged by nuclear war, who have retreated into metal boxes, and to live inside another metal box. As for the Nazi ideal of Aryan physicality, that belongs to their old enemies, the Thals.

The Thals are stand ins for the Jewish. Displaced, they wander the planet in search or settlement, and their name is a suffix common to many Jewish surnames. But again, you can push this allusion too far. It’s enough to say that Thals are sympathetic hero types, but their fair skinned good looks bring an unwelcome hint of body fascism to proceedings. Beautiful is good, ugly is bad.

But the Thals are also pacifists, which leads the story to its turning point, when school teacher Ian Chesterton (William Russell) must convince the Thals to fight the Daleks, so that the time travellers can regain a lost TARDIS component. “Pacifism,” says Ian, “only works when everybody feels the same,” basically giving voice to the story’s mission statement. The sequence where he provokes chief Thal Alydon (John Lee) into fighting by threatening to take his girlfriend to the Daleks, can be read as Ian proving to the Thals that pacifism has its limits.

In the end, it is fear which spurs the Thals to dump their beliefs and go on the offensive. As Alydon says, “The Daleks are strong and they hate us. And I am sure they will find a way to come out of their city and kill us.” He’s right about the threat the Daleks pose (inside their city they plan to flood the planet with radiation), but how odd to think that the predicted threat of an attack has managed to convince the Thals of the virtue of a pre-emptive strike. By the time the TARDIS crew have left, our heroes have taught a peace loving race to be warriors again. Which is to say the least, an unusual position for a Doctor Who story to take.

4.

Elements of this story endure. Tristram Carey’s music with its submerged bass note thrum turns up again. Brian Hodgson’s sound effects for the Dalek city are still being used in new Who. Terry Nation reuses plot elements in future stories like repeated guitar riffs from a hit song. It’s absolutely right that Into the Dalek, and stories yet to come, continue to look back to this bedrock story. It may not have changed the Doctor, but it sure did change Doctor Who.

ADVENTURES IN SUBTITLING: “Capsule ready to go critical” grates one Dalek to another in the final episode. “Perhaps you’re ready to go critical” guesses the subtitles, which seems an odd suggestion to make.

LINK to Gridlock. Both feature subterranean sanctuaries from ravaged worlds above.

NEXT TIME: Why is your face all coloured in? It’s our first Capaldi story Time Heist.